Functional Bodybuilding: Foundations and Connections

The sport and underlying physiological tenets of modern Bodybuilding have, since the 1940s, grown into a global juggernaut. Popularized by early icons like Reg Park and Sergio Oliva, and ultimately permanently cemented into the foundation of Western popular culture by Arnold Schwarzenegger; bodybuilding, as a training methodology and sport, generates billions of dollars and holds a global audience of fans and participants. Yet, quite different from its modern incarnation, where larger-than-life men and women dehydrate themselves out to near fatal levels, prior to painting their bodies and posing on stage for judgement, an earlier incarnation of the sport placed emphasis not simply on aesthetics, but also upon underlying physical strength and athleticism. It is from this, a notion that spans back to classical Greek connotations of the natural beauty of the human form, that we can find elements of value to current fitness regimes. It is ultimately from this that we derive the idea of Functional Bodybuilding and its tenet of “Look good, move well.

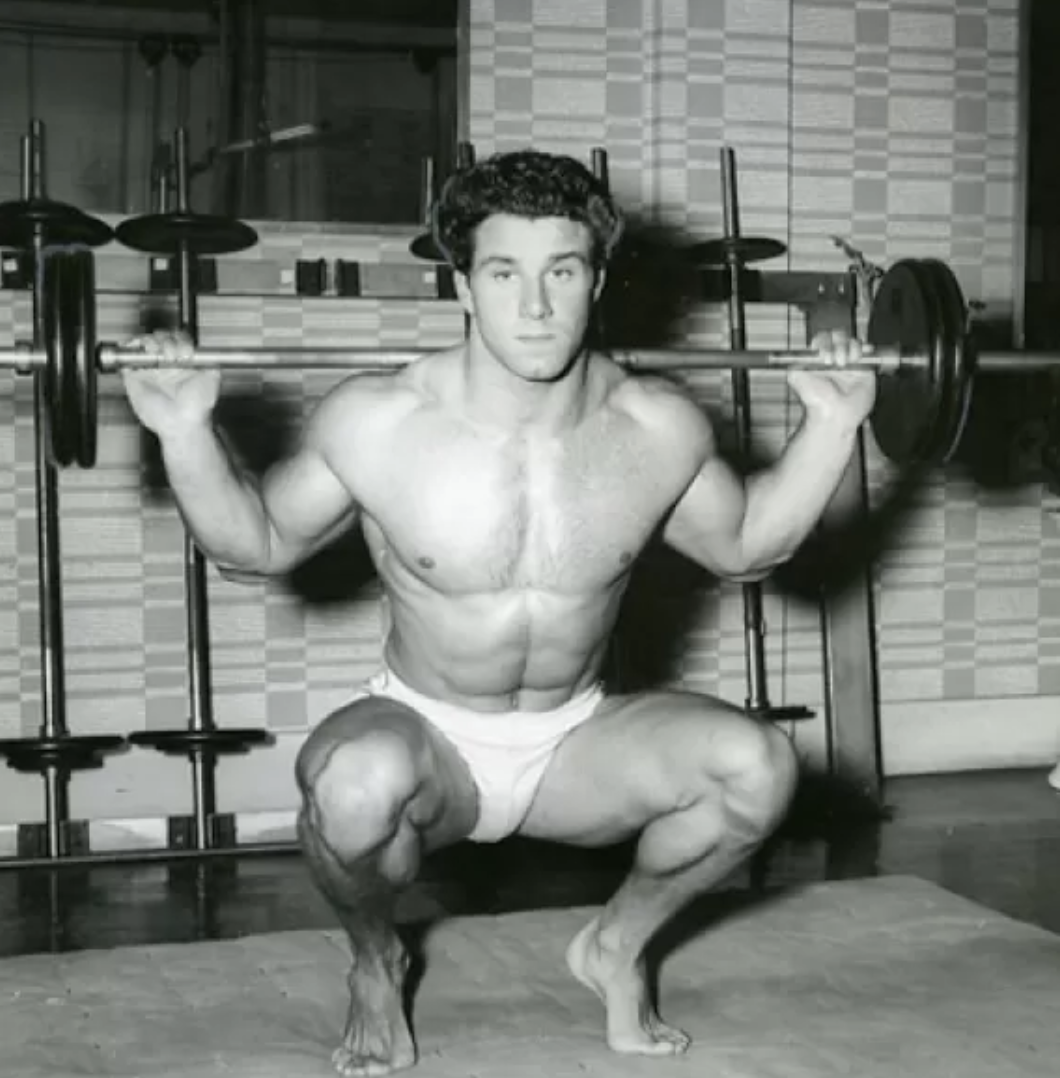

”Practitioners of bodybuilding were not always synonymous with partial range-of-motion isolation exercises that had little functional application in daily existence. Franco Columbu, a two-time Mr. Oympia (the Super Bowl of modern Bodybuilding) was a powerlifter by training; deadlifting 750, squatting 665, bench pressing 525, and clean and jerking 400 at 5’5” and around 185 pounds. In another generation, he may very well have made a name for himself in the Sport of Fitness, rather than that of the sport of aesthetics. Schwarznegger himself sntached 243, clean and strict pressed 264, clean and jerked 298, benched 440, squatted 545, and deadlifted 710. And yet, these men were and in many ways remain the paradigm of their respective sport. Long before functional fitness executed at a high intensity revolutionized the fitness industry and the study of exercise science, these men, along with those who preceded and succeeded them, mastered the delicate balance of strength, health, aesthetics and functionality.

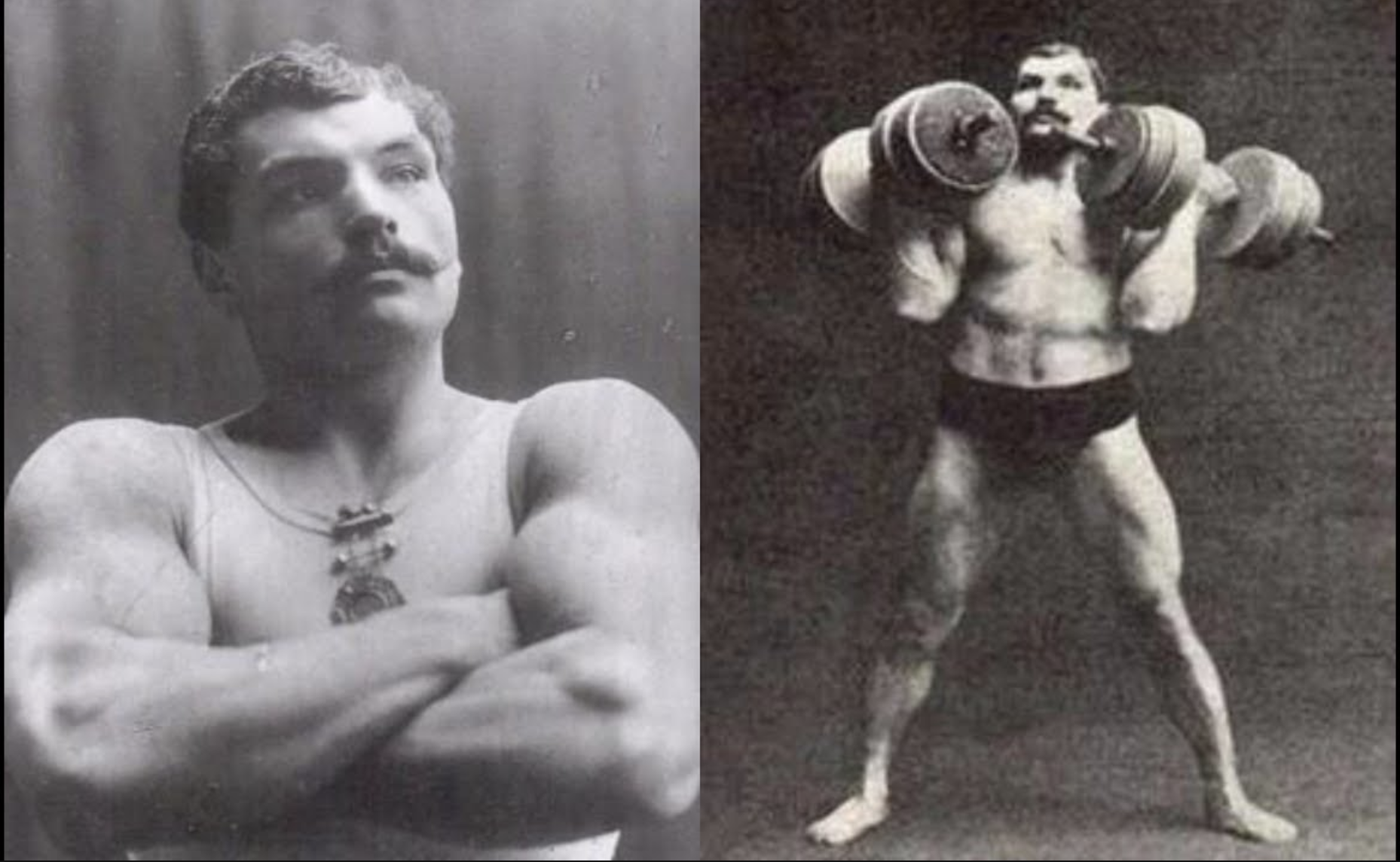

Even before Columbu and Schwarzenegger, turn-of-the-century pioneers of what came to be known as Physical Culture like Eugene Sandow, George Hackenschmidt, and Arthur Saxon were popular icons of their time not because they pioneered the use of spray-on tanning products, but because they used their strength, athleticism, and performance prowess to shed light on the 2500 year-old notion of what the human body could and should look and perform like. Not dissimilar to modern Crossfit Games athletes, they were seen as the physical ideal; the pinnacle. What could be aspired to, with consistent, hard work.

The concept of combining tenets of gymnastics, weightlifting and powerlifting, and aerobic capacity, while expanded to a global level by CrossFit, in fact has its roots it turn-of-the-century gymnasiums and lyceums that sprung up in the U.S. and Europe. Ironically, these gyms would not look foreign to a CrossFitter, as they were populated with suspended rings, kettlebells, dumbbells and barbells. Emphasis was placed on physical strength, not only through the movement and manipulation of external loads, but also via mastery of gymnastics and calisthenics.

Participants worked out together, often competing with one another in lifts or skills. Aesthetics were always a goal, but insofar as it was seen as being synonymous with health and vitality. Yet, despite the efficacy of these gymnasiums in promoting health, they had almost entirely disappeared by the 1950s; replaced by comparatively plush, “health clubs.” Their rings and barbells pushed to near-extinction by a preponderance of cabled, range-limiting, cam-operated machines of every form and purpose. Inoffensive and largely self-evident, with regard to use, at the expense of efficacy.

The disappearance of this method of physical exertion coincided, along with other widespread lifestyle changes (mostly related to the diet) to the precipitous decline of American health.Quite unfortunately, the connection between good movement, functional strength and a targeted diet in promoting not only optimal aesthetics but also optimal wellness was also ultimately largely lost on the modern population of bodybuilding practitioners. Largely on the contrary, the goal of putting on “mass,” i.e., hypertrophy (muscle growth) came largely at the expense of real strength or functionality. Relative to the deadlift, pull-up, strict press, and squat, curls and lateral raises have not only little use in everyday life, but also in the pursuit of long-term health, though they can be effective, purely from an aesthetic perspective. Largely in reaction to this, the functional fitness community tends to, at best, be skeptical of bodybuilding. Yet, a new method; Functional Bodybuilding, bridges the gap between non-functional movements that fail to elicit neuroendocrine responses in the body and the other extreme of “intensity at all costs,” which may not prove sustainable on an extremely frequent, long-term basis.

Developed and pioneered by Marcus Filly and his coach, Mike Lee, the methodology focuses on improving movement, positioning, and absolute strength to not only better prepare the body for intensity, but also to allow it to effectively recover and rebuild itself after bouts of heavy intensity. At the highest level, it appears to be the most appropriate off-season protocol for competitive athletes: relatively low-intensity development of positioning, skills, and absolute strength; prior to giving way to in-season training that focuses more on intensity, as required by an athlete’s given sport. However, Functional Bodybuilding practices and prescriptions also find a welcome home as part of the training program of individuals with goals more focused on gaining functional physical strength, improving body control, and aesthetic appearance.

Not dissimilar from the CrossFit methodology, with which it shares many traits, it is appropriate for high-level competitive athletes and those entering the gym environment with little to no previous physical training or underlying understanding of movement. It is all a matter of scale. Far from being new revelations, the methodology’s liberal use of rest/pauses, tempo, varying repetition ranges, isometric holds, and eccentric loading have been widely used in the bodybuilding community for generations. Similarly, its emphasis on tying nutrition to the triad of health, performance, and aesthetic goals traces its roots not only to those of CrossFit, but also to what bodybuilders have been doing since the 1960s. It is not a new fad, such as rowing-, cycling-, or boxing-only fitness studios; but instead the articulation of the centuries-old practice of Physical Culture. The confluence of strength, intentional practice, performance, and aesthetics.

Check out our Dublin, Ohio Gym Build Class or Remote Coaching for work on Functional Bodybuilding with a Friendship Coach.